I arrived in Cartagena in the early afternoon. The outskirts of the city are tall white apartment buildings, a bit too Miami for me, but further in is the old town, surrounded by an ancient stone wall. My bus dropped me outside the walls, so in the afternoon heat I meandered between tall vacation apartment towers and beneath the great stone gate leading to the old town.

You may remember me writing, early on in these diaries, that I wanted to discover the land that Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote about. Bogota and Medellin looked nothing like the fantastical towns he described, and I was disappointed in Colombia at first, believing that I’d come here with expectations back solely in fantasy. However, upon crossing beneath that broad old gate, a new world opened up to me.

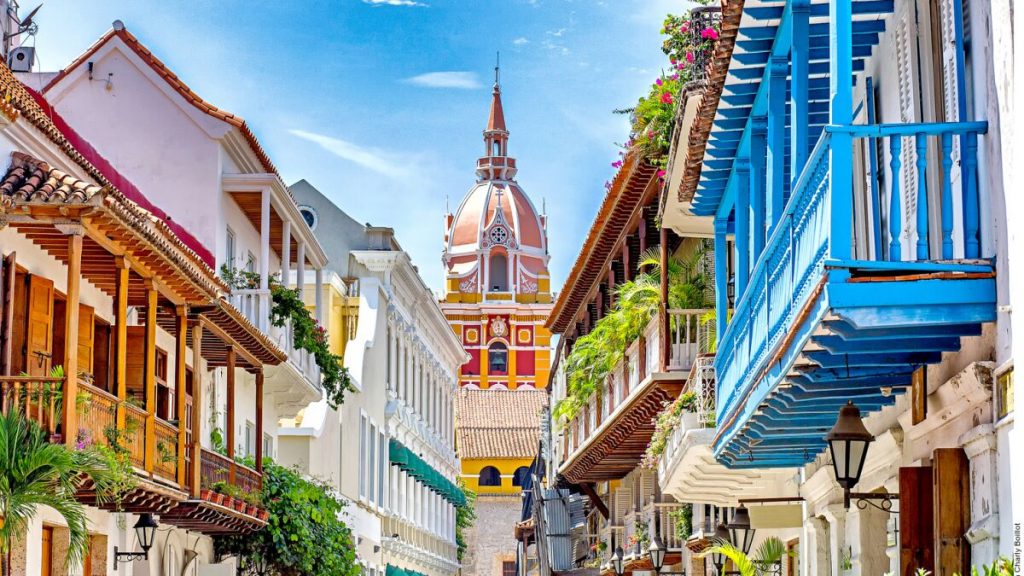

Cartagena’s old town, composed of the districts Centro and Getsemani, is a warren of narrow streets lined with old colonial buildings,all clung with flowering vines and painted balconies. Horse drawn carts clop down the streets, and fruit vendors sell mango and papaya on corners. Lightbulbs cross back and forth in a tangle above, and wooden shutters keep the heat of the day out of peoples’ homes. Wooden awnings shelter the terraces above street level, and colourful murals of animals and music scale the sides of shops and buildings at every turn.

I grew emotional as I walked to my hostel, past gnarled trees growing up through the pavement hung with lilac flowers, drifting down on the summer breeze. In town squares, old men were reading newspapers on benches beside towering white statues of soldiers with sabres drawn. Yellow birds fluttered down from rooftops, and across the square an enormous green iguana, an orange fan across its head and down its spine, crept along the grass and up a tree trunk. I passed a man sleeping beneath a parrot on a perch; it squawked as I passed and woke him up. In the town square in Getsemani a warm yellow church dominates everything, its vibrant mango hues showing even brighter against the black grime and the scars of peeling paint that scatter its surface. Magic hangs in the air.

This is it! I told myself. This is the place he wrote about!

My four days in Cartagena were blissful. With a handful of kindly hostel friends, I spent several days exploring the walled-off town at a leisurely pace. The rest of the city, the city beyond the walls, is dangerous for tourists. Inside Getsemani, however, you’re good to walk around alone, at night, however you please. You still need to be vigilant of course – always, on this rough-around-the-edges continent – but you’re not in danger.

I was thrilled to discover that Marquez wrote Love In The Time Of Cholera based in Cartagena; it explained why the city felt so inviting and familiar, as though I’d been there before in a dream. Crossing one afternoon beneath the huge gate, the Torre del Reloj, ancient entrance to the city, I found a bookseller. His stall had many works of Marquez, in many languages. I told the bookshop man about my love for the author, and he picked up a novel I’d not read: The Autumn Of The Patriarch.

“It’s a very difficult novel to read, even in your own language,” said the bookshop man over his spectacles. “Because there is no point.”

“Ah, right. So it’s a sort of literary story, without a real plot.”

The bookman shrugged. “Yes, there is no point. It goes on and on, and there is no point in any of it.”

“But it’s not about the point right? It’s about the magic of reading it.”

“Yes,” he agreed. “But it’s very hard. Because there is no point.”

“Er, right.”

Anyway, after several minutes of this apparently nihilistic literary discussion, he gave me the book to flick through and it turns out he meant there were no full stops.

I asked him if he knew of any locations within the vibrant port city that feature in Love In The Time Of Cholera.

“You’re standing in one,” he told me. “You see those arches across the square? That’s the spot where the two lovers are finally reunited at the end of the story, after forty years apart.”

My eyebrows rose an inch and knitted together in the middle.

“Really?”

The bookman nodded, and I felt emotion swell behind my eyes. One month of searching and I’d found it: the magical, colourful, swashbuckling world I knew existed, at long last. It was real.

*****

With hostel friends – a delightful German couple and a kind French girl – I headed out one night for dancing. We began with drinks in the square before the yellow church in Getsemani; every evening the plaza is alive with little stalls selling drinks and hot empanadas, lined with bars and cafes, with music and tourists and locals alike sitting around drinking and laughing. Later on we headed to a place called Cafe Havana. It’s a salsa bar, Cuban-themed, and stepping off the street and through the grand double doors feels like teleporting a thousand miles across the Caribbean, straight into the heart of the bars in Old Havana, across from the windswept malecon. A raucous band was on stage fronted by three tall black women, laughing as they sang into their mic stands between frenetic dance breaks. Behind them a full band blared with trumpets and crashing drums, and Cuban salsa legends were plastered in print across the walls. There were broad spinning fans overhead and everything was dark wood, rich in colour and texture, and the bar was an island in the middle of endless winding, looping dancing. I was in love.

The German couple danced together – and danced well – but the French girl and I didn’t know how to do more than a basic step, and so satisfied ourselves with a beer each and people watching. When it closed we walked home together, happy.

*****

Now, when people ask me about my favourite experiences on this Latin American trip, I usually mention the cenotes in Mexico, the Day of the Dead, the Lucha Libre in Mexico City, the eruption of Fuego in Antigua. People nod along to this: yes, of course, of course those would be the highlights.

And then I say ‘Oh, and then there was the naval museum in Cartagena,’ and people go: …what?

*****

It was a sunny, hot morning and I wanted to do something cultural.

To start the day I got up early and had breakfast with my French friend, Elo. We went to a cheap little cafe, and then we explored a few blocks of the city together. We came to a green park, a few hundred square metres in the centre of the old town, and within this square we saw a group of people clustered around a tree. We thought there might be a weird bird or something, so we pootled over. But no birds: monkeys. Tiny ones. They were jumping through branches and palm leaves, hooting and munching and playing with one another. The canopy above our heads was alive with them.

When we’d spent a few minutes watching the little monkeys play (How did they get there?) we made off through the park again, passing white stone busts of long dead thinkers. We saw another crowd around a tall palm tree, so we went to see what the fuss was. This time, however, was even cooler: a sloth.

A sloth! I’d wanted to see a wild sloth since I started my trip! I stood back, craning my neck to look up at the shabby gray creature relaxing at the top of the palm. I was in awe. For a while, at least. The thing about sloths is that, quite famously in fact, they don’t really do much. They’re cool to spot, but then you’re essentially stood watching a motionless ball of sentient hair for the next five minutes. So we left.

We relaxed in a beautiful park for a while (the one with the gigantic iguana) and then Elo wanted to go shopping for trinkets, an activity I passionately hate. We agreed to split up for a couple of hours and reconvene for lunch later. That’s when I decided I would visit the naval museum.

I don’t particularly give a damn about the modern navy. I’m sure they have a lot of fun sailing around and all that, but the imagery doesn’t spark my imagination. I wanted to go to Cartagena’s naval museum because they have a huge exhibition on pirates.

I’ve loved pirates since I was a kid. I don’t know what specifically it is. They’re just… cool. More liberated than cowboys, more rebellious than knights, more jovial than ninjas, more charming than vikings. The pirate life (that is, the romantic fairytale illusion of it, rather than the rather severe reality of scurvy and splinters) is one of adventure, glory, heroics, and unlimited freedom. All that sun, all those strange new horizons. The danger and the theatre of it all. Smoking beards and skulls on flags, pistols and rattling sabres and tri-corn hats, leaping whales and glittering sunsets and buried treasure. I just adore it. Obviously.

I bought a ticket to the museum, and I spent one minute reading the exhibits before leaving: everything was in Spanish, and I may be fine at talking to shopkeepers in their own language but I can not read complex narratives about the foundation of a colonial town four centuries ago. Back at the reception desk, I apologised and asked for an English-speaking guide. And what a guide.

His name was Miguel. Middle aged and silver-haired with laughter lines, Miguel lives in Cartagena, and his passion for the city’s history is infectious. For the next two hours, Miguel whizzed me around the museum like a sweeping ballroom dance, pausing before mannequins of pirates to give me their history and unique details of their lives. He made damn sure I was listening, too: testing me on key facts, dates and names as we progressed.

My German friends joined after 30 minutes (I’d invited them, they were running late), and they too were swept up in Miguel’s fantastical, flamboyant storytelling. Aided by the maps, mannequins and plastic models of the museum, he told us tale after tale of the city’s turbulent history. We heard of cannibal tribes, of glittering armadas, of cruel slave ships and bloody city sackings, of Sir Francis Drake and cannonfire, of a one-eyed, one-armed, one-legged French pirate captain, sieges and secret passages, and best of all, ghosts.

Of an insane aristocratic Frenchman who mercilessly ransacked the city while it was in its infancy, Miguel told us:

“They say if you are walking within the city walls at night and you see a shadow move in the corner of your eye, it’s his ghost, still stalking the streets.”

I was completely besotted. I felt like a kid, rapt with attention. There were ghosts everywhere, if Miguel was to be believed. He told us of the cholera epidemic that gripped the 19th century (Marquez!!! Ahhh!!!), and of the bodies buried beneath the museum. He showed us a waxwork of a woman lying sick with cholera, and he told us that if we watched closely, we might just see her blink.

When we’d reached the end of the piratical section of the museum, Miguel took us upstairs. There was a large bell at the bottom of the stone staircase, and he made us ring it loudly before going up.

“They say there’s a ghost that haunts this staircase, and if you ring the bell he lets you have a headstart before he pushes you and you break your neck. Quickly! Run up the stairs! He’s coming! Quickly”

We left the museum with enormous smiles on our faces. It was just – I don’t know. Just sheer childish joy. I hadn’t felt anything like it – that totally uninhibited ‘hey let’s take our Playmobil up on the roof and throw them off into the trees’ silly childish creative innocent fun – in years and years. I was on a high for the rest of the day. We went for drinks and we went for food, and the sunset was beautiful and everything else was beautiful too.

The second floor of the museum was all modern naval exhibits. I wasn’t interested in learning about these, and thankfully Miguel wasn’t interested in teaching about them either. Instead, he asked to use my phone. He turned on the camera and ushered us into a life-size replica of the command deck of a Navy ship. He gave each of us a role and a line to say (the couple were fantastic fun), and then filmed us acting out silly little scenarios: Captain! We’ve spotted an enemy ship! What do we do? Fire the cannons! Full speed ahead! Aye aye captain! That sort of thing.

We left the museum with enormous smiles on our faces. It was just – I don’t know. Just sheer childish joy. I hadn’t felt anything like it in so long – that totally uninhibited ‘hey let’s take set up our Playmobil soldiers along the river bank and then bombard them with ‘cannonballs’ made of pebbles’ silly childish creative innocent fun. I was on a high for the rest of the day. We went for drinks and we went for food, and the sunset was beautiful and everything else was beautiful too.

One of the most golden, enjoyable, blissful afternoons – not just of my trip, but of my whole life.