In Which Edgar Has An Incident

I had not made it two feet when a brilliant white light seared into my retinas, rendering my eyes useless. I staggered forward, flailing wildly, stupid and helpless.

“Selladore! Glob! Ugh – Edgar! Thy king is blinded, help!” I called out.

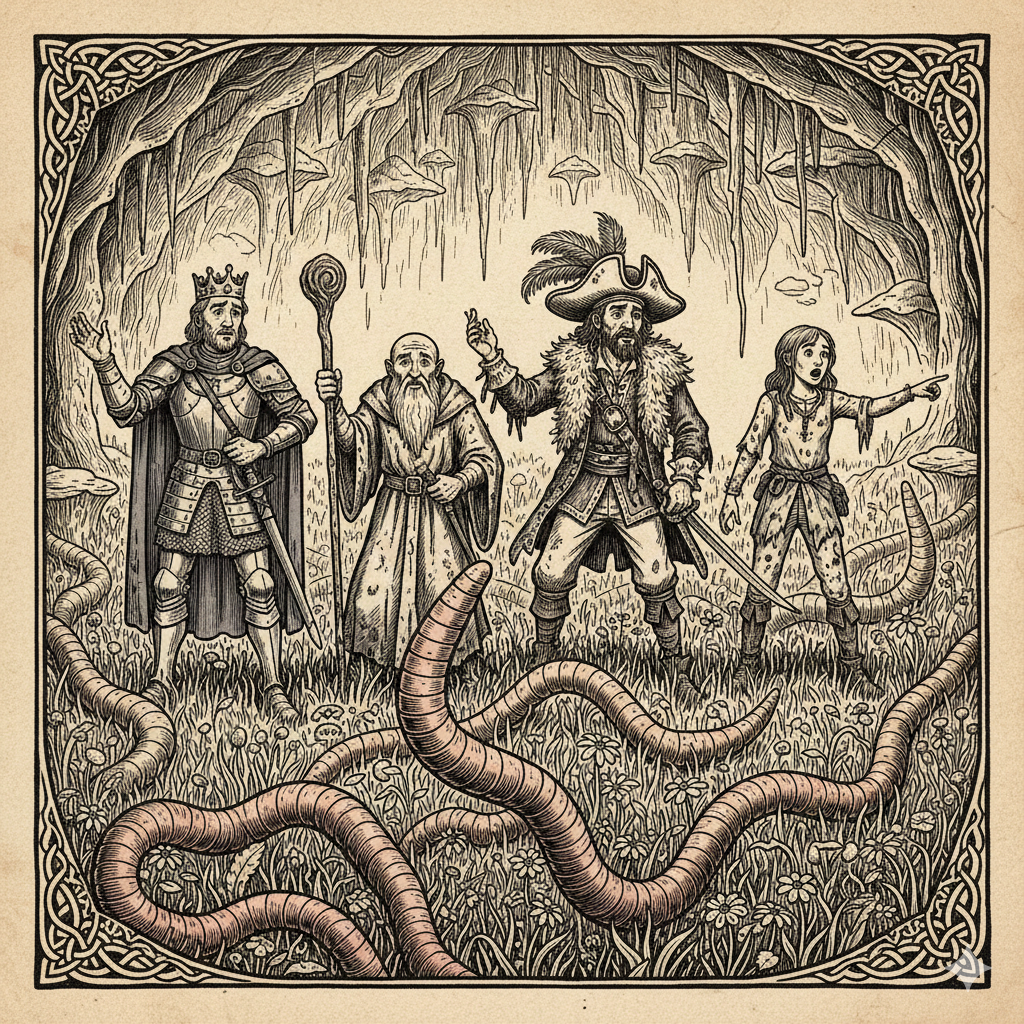

They must have run in and suffered the same fate; I heard the chorus of their shrieks. We four blinded fools clattered into one another as we raced around whatever chamber we were in. The roars of the unseen creatures were deafening, coming from every side. I tripped over something soft and furry, sailed arse-over-bosom through the air, and landed in a clanking heap on the floor. My sword fell from my grip, leaving me defenceless. I felt hot, stinky breath in my ear, and span around to punch with all my might whatever beast was coming for me. My armoured fist connected with the monster’s fleshy hide, and I heard a squeal. The monster backed away as I rubbed my eyes hastily, urging them to adjust to the light.

Images came back slowly, blearily – colours and shapes. As my vision reassembled itself and I was finally able to see, I gasped. The others were still rolling around in the dirt, but as seconds passed they too lost their breath in wonder. In the dark depths of the earth, on the ninth level of the long-deserted Mines of Mupplecock, hidden away behind a colossal stone door, was a meadow filled with giant earthworms.

For a long time, nobody said anything. I glanced down and saw an injured worm rolling around on the ground, winded. I realised I had lamped it in my blinded thrashing. The worm slunk away to join its friends, who were all regarding us with interest. Or at least – it seemed they were (worms don’t have eyes).

Selladore sidled over and elbowed me.

“I’ve seen nothing like this, not across all the seven sands,” he said.

I hadn’t either. I glanced up in search of the source of the light, and saw that the chamber was truly enormous; several acres worth of space, with the outer walls rising hundreds of feet above and at the very top was blue sky, spotted with little puffy clouds. After hours in pitch dark, it was a marvel. The air smelled fresh! There was a breeze! Water was flowing through the meadow, a clear, sparkling stream running through the grassy hills. O what paradise! O what heavenly pleasure! O what– hang on– worms?

My initial rush of childlike wonder left and slammed the door on its way out. I looked pleadingly at Glob and Edgar, who looked pleadingly back.

The worms roared, but without the distant building echoes of the mineshafts, the roar sounded far smaller, more like a series of happy yawns. All across the meadow, from little soil mounds, worms wriggled, popping their heads out for a look, then loping their way towards us clumsily.

We watched the procession of worms quietly. They stopped a few feet before our bamboozled company, and a three-foot elder-worm with a scar across its face (Face? Head? End?) rose up on its… body?… and nodded a greeting.

“Hullo,” it said. “My name is Horatio.”

“Worm,” I replied.

I must admit this response was not quite up to par with my usual diplomatic introductions — but come on! I couldn’t think of anything else to say; I was stuck on a mental merry-go-round. Horace smiled – or appeared to smile; it turns out it’s quite hard to tell what a worm’s expressions are. They don’t really have eyebrows.

“We are not worms,” it said, patiently.

I frowned, running an eye over the fleshy pink assembly before me.

“Right.”

“We’re not,” said Horatio.

“Yes, no, of course. So…”

“We are cursed!” cried Horatio. “We were magicked into this form! We used to be…”

“Dwarves,” finished Edgar.

“Edgar, shut up,” I snapped. “I’m sorry Horatio, he’s very rude. Please continue.”

“Dwarves,” said Horatio.

“Shit.”

Oh how I loathe it when he’s right.

*****

Once I’d explained who we were and where we were going (that is, to shank that bastard prince and safe my gorgeous wife), Horatio walked us down the winding path into the meadow. As we walked he launched into the tale of how his people had met their fate.

Note: Horatio didn’t walk, obviously. You need feet to walk. I’m reluctant to write ‘slithered’ though, because that makes him sound like a snake. Do we have any verbs specific to worms? Worm verbs? I don’t know. Wriggled — no. Worms do wriggle, of course, but when you picture a wriggling worm you think of thrashing about, not steady movement. Rolled? No. Lolloped? No that’s for camels and sheep. Squirm? Inch? Crawl? Twist? Hmm.

Undulate? Surely not. I can’t put ‘Horatio undulated along the floor,’ can I? It sounds like erotica, for heaven’s sake. Oh, bollocks to it. Worm is already a verb, isn’t it? ‘He wormed his way out of trouble.’ Infinitive: to worm. Horatio wormed along the path. There — whatever.

Erm. Where was I?

Oh yes.

“We were once a thriving and proud people,” Horatio began. “But in our pride, we grew greedy. We dug deep into the mountain our insatiable hunt for precious stones, hollowing it out, exhausting it – and yet we cared not. There were some who protested of course, claimed such hubris could only end in tragedy, but we told them to be silent. Progress – that was all that mattered!”

“Goodness,” I yawned.

My stomach was rumbling. When did we last eat? Gods, it must have been hours ago. All that downhill-walking and no sturdy nosh to stouten our gait. Honestly, I really felt just knackered.

“There was no stopping us — until one day, a vision appeared to us, a shimmering figure, haloed in light! It was the spirit of the mountain itself, come to warn us of the doom toward which we were hurtling. But still, we did not heed the warning. We dug on, ever hungry for more. Again the vision appeared to us. This time, it said, I really mean it. Stop digging or you’ll be sorry. But we did not stop! Oh, we could not stop. Digging was all we knew! And so… on we dug.”

“On we dug,” I nodded, rifling through my rucksack to find something to eat.

There was an apple in there, but it had gone a bit brown. I don’t like brown apples really – they’re too soft and sweet – but ugh, it would have to do.

“And again the spirit appeared! Go back! it cried. For goodness sake! Knock it off! You’re digging way too much! And of course, we did not listen. Fifteen more times the spirit appeared to us, and fifteen more times, we dug on.

“Finally, however, it seems the spirit tired of our endless lust for shiny objects buried in muck. It flashed up before us a final time, right as we knocked through into this meadow – the heart of the mountain. Fine! It said. Sod the lot of you! And there was a mighty bang, and quite a lot of glitter, and when the glitter had settled, our people had been turned into worms forevermore.”

“That is so crazy,” I said, trying to get a bit of apple skin from my teeth.

Glob elbowed me in the ribs.

“Pay attention you knob.”

I coughed, blinking, and willed my brain to remember whatever the little worm had been going on about.

“Right so… lots of digging, spirit appears, cursed. Alright. So, er… why didst thou not simply stop digging?”

“Alas!” yelled Horatio suddenly, giving me a start. “Don’t you see? We really, really wanted more gold.”

“Right, yes. But… to do what with?”

“Well,” said Horatio, as he oozed along the path, “the uses of gold are many. It’s a complicated – er – it’s a complicated economy, you see.”

“In what way?” I asked.

“Market forces, investment. Growth. A commodity such as gold is really invaluable in, you know, all sorts of… transactional – er – increments. And ultimately, it was really sort of inevitable that– we, I mean, we couldn’t just… I mean—”

I watched the elder-worm with an eyebrow raised.

“Right.”

“Our entire economy was based around the wealth we uncovered in these mines! Our society would have gone all to bits if we stopped digging. We’d have been out of work! Think of the shareholders! If we didn’t create value for them, they’d have taken their business elsewhere. They’d have left us in chaos!”

“No, yes, well we wouldn’t want that,” I frowned, glancing around at the worm colony.

Horatio cleared his throat (wherever that was situated – as far as I was concerned his whole body was a throat) and avoided my gaze.

“Look, it’s – uh – it’s a complicated issue. It’s multi-faceted,” said Horatio.

“Of course,” I nodded.

*****

Shortly after we arrived at the worm village. ‘Village’ was their word, not mine; I’d probably have said ‘nest’ or ‘pit’ to be honest, because the whole thing was very slapdash and muddy, but I didn’t want to offend them because I wasn’t sure whether worms had teeth – or for that matter, what they liked to eat.

“What do worms eat?” I whispered to Edgar, as Horatio indicated for us to sit down around a low wooden table.

“Bits of mud, I think Sire,” said Edgar, in a sharp reminder that I should never bother asking for his opinion on anything ever.

Across from us, Horatio looped his long naked disgusting body onto a small chair and aimed what I assumed was his face at us.

“We do not often have guests in our meadow,” said Horatio. “As an elder, I have decided we will offer you a taste of traditional Dwarven hospitality. Let us dine!”

At this, a handful of lower-worms wheeled out clatter of plates on a little cart, covered trays and plates glittering in gold. I lifted the lid on mine and found what appeared to be a great mound of– unfortunately I can’t think of any other word than ‘sludge’. I sighed and pinched the bridge of my nose.

“I’d sooner have my eyes gouged out than eat a morsel of this,” I whispered to Selladore. “Let us get out of here.”

“Agreed,” said the pirate, prodding the globules of matter on his plate with a mortified fork. “Perhaps we can just make our excuses and—”

“And while we eat,” cried Horatio, “we shall perform for you an opera! It is one of our most beloved tales, performed only once a decade for our most esteemed guests. It is the story of Grimbus, the runaway Dwarven maiden, and her doomed romance with Plunt, the armourer’s son. It is rather a short Dwarven opera at just over four hours in length, but I hope you will enjoy it all the same.”

“Oh, well that sounds… good,” I said, quietly.

*****

The opera was very weird and shit, obviously; in my dreams for the next hundred years I will be hounded by the sight of singing earthworms performing courtship rituals. I nudged my sludge around my plate for several hours, waiting for moments when nobody was looking to sling forkfuls over my shoulder into the meadow.

It was as we entered the fourth hour of the opera that I looked around and found Edgar missing: his seat vacant, his plate (horrifyingly) empty. Excusing myself for the bathroom, I hurried away from the table to find my missing captain.

“Edgar?” I hissed, jogging betwixt the mounds and simplistic twig-hovels of the meadow. “Edgar, thou mighty dunce, where art thou?”

And then I saw him: across the meadow, hammering away at a wall with the hilt of his sword. I watched him wedge it into the rock and begin to pry at a glittering jewel set within.

“Edgar, what doest thou? Pack it in!”

But it was no use: he could not hear me over the echoes of the worm-opera.

Finally, as I drew near, he turned and saw me.

“Oh, hello Sire,” said my captain. “Look at this! Thought I’d mine a little souvenir before we leave this place.”

“Edgar, I swear to the Gods I will pluck out thine eyes and mash them into a soup if thou dost–”

But — alas: before I could finish my threat, Edgar had plucked the glittering nugget of gold from the cave wall. He hoisted it aloft to inspect it, triumphant – but only for a moment. Suddenly, with a loud bang and a puff of purple smoke and a little shower of glitter, the gold was gone. And so was Edgar.

“GAH,” I howled, falling to my knees in horror.

I groaned to see the captain of my guard go up in smoke; half because despite his idiocy he was undeniably brave and I quite liked his company, and half because the captain of my guard being exploded within a month of his being hired reflected very badly on my supposed eye for talent. However, as the thick cloud dissipated, it became apparent that dear Edgar had suffered a far worse fate than being merely exploded: with a great, heaving sigh, I saw that he had been turned into a fucking worm.