In Which I Tell A Lovely Story About My Gorgeous Wife

The next morning we waved goodbye to the shrinking earthworms below us as we ascended up and out of the Mines of Mupplecock. Glob and Selladore were operating a large hand crank on a rickety old elevator made of frayed rope and gnarled wooden planks. The worms in the meadow had no use for it, obviously; worms don’t have hands. I was clinging on for dear life as we rose, as each turn of the giant cog sent a threatening shudder through the knackered machine. It didn’t help that we had the fat useless lump that was worm Edgar dangling below, suspended from a bundle of rope because he couldn’t fit aboard the platform.

I glanced over the edge, and saw Edgar dangling serenely over the side of the elevator, quite vacant expressionless and vacant, the rope bound securely around his torso. He was rebounding gently off the face of the cave wall, but didn’t seem to mind much. I leaned over the side of the elevator and waved down to Horatio and the worms below, gathered on the highest hill in their enchanted meadow.

We reached the rim of the sinkhole, clambered out of the elevator basket, and hoisted Edgar up over the lip to join us. We stood assembled and surveyed our surroundings as a welcoming breeze tussled our hair. Gazing east, towards the horizon, I saw the deadly carbon monoxide swamps of Noople that we had circumvented via the mines. To the west, a great grassy plane lay before us, with the Sea of Pìss (pronounced peace) presumably beyond, and my Astra somewhere over the horizon, awaiting her love.

Our somewhat-less-bold-than-previously company mounted our steeds (which had indeed accompanied us through the mines, despite me forgetting to mention them), and set out once more across the earth on our noble quest to rescue sweet Astra.

We rode abreast across the plane, parting the grass around us like scissors through emerald velvet. The air was alive with little birds and lazy insects, and areas of the grass chirped and buzzed as we moved through it. It was a fine summer’s day; the sun beating down, idling clouds recumbent in the ether, pollen in the air making us sneeze. We rode for three hours, a-chooing and a-tanning, idly quaffing mead and nibbling crisps and sausage rolls.

“I say,” I said, breaking the basking silence, “did I ever tell you about Astra and I’s honeymoon?”

“Yes,” said Glob. “Fifteen times.”

But lo, I did not hear the shit-caked stable lass, for I was already lost in memory.

“Ah! T’was eight years ago next November. After the wedding, which as you know was a bit of a fiasco, Astra and I set out on a two-week jaunt over to the kingdom of my aunt, Queen Kundera. I wanted to go for longer, but Astra told me I needed to be present as king in order to keep order, and I suppose she had a point.”

“Aye, there were a big fire in’t docks when you were gone. And bandits took over the southern quarter,” said Glob.

I blinked at her, mentally noted her comments down, punted them into the cobwebbed section of my mind’s library labelled ‘Wilful Ignorance’, and continued.

“Verily! Kundera is a cantankerous old boot, but Astra and I were giddy to experience the famed tranquillity of her hanging gardens. We decided that we would find a way to avoid her for the majority of the trip. So, upon our arrival, I didst creep into the yard to kidnap the castle’s cock! Ho ho, yes! And I released the thing into the forest to be free. Without her morning alarm bird, old Kundera woke up after midday every morning that fortnight, never quite understanding why, and by the time she had become dressed, Astra and I had spent each morning in the magnificent serenity of the hanging gardens, shagging like rabbits. In the water fountain, under the hedgerows, in the treehouse, in the wagon, in the barn, on the trestle table while the waiting staff were setting it for breakfast. Gods we went at it a lot. Christ.”

The others didn’t appreciate this story as much as I thought they would. I suppose you had to be there.

“O!” I finished, as a wave of quiet sorrow rolled all the way up my body and into my mouth and from there to my headbrain. “I doth miss it, I doth.”

“Look!” called Selladore, which at first made me incredibly angry because I thought he was just bored of my story and not listening.

As I followed his outstretched pirate finger, however, I saw a sight that penetrated my heart with the long, thin dagger of awe: the sky was too low. The sky was too low!

The grassy plains ahead of us did not quite reach the horizon; there was an odd strip of cold blue sky between them. It was then that I realised that it was not the sky at all that we gazed upon, but the terrifying frozen ice-waves of the Sea of Pìss.

*****

“Unravelling endlessly goes the corpse-sea, the frozen mass of a billion tons of water, rigid and snow dusted and serene, yet below the icy surface, where the eternal cold cannot penetrate, O there be life! Down in the lurking waters, primaeval and angry, there be nasties. O! The nastiest dread-fish ye can summon up from the dankest recesses of ye minds, tendrils and tongues, eyes waterlogged and empty, brine and blood and twenty hundred gnashing teeth, they be ne’er more than a couple of metres beneath the boots of any traveller mad or brave enough to attempt crossing. Tread lightly, all ye who would seek to cross the Sea of Pìss, for if ye tread anything but, ye’ll ne’er tread again.”

“Selladore, what the hell?” I cried, yanking the dusty old tome from his hands. “Edgar was bad enough, but not you as well!”

“I didn’t finish the passage! Let me finish it. You can throw it away after, if you must,” the pirate protested.

“Fine,” I sighed , flicking to the right page. I read the last small paragraph aloud:

“A note: if ye be seeking a haven as ye traverse the creaking ice, seek out the seatown of Galanthus. On the sturdiest ice in the centre of the sea, there be the only place for a hundred leagues where a weary bastard can drink a mead or three and enjoy a comfortable trip to the privy without contracting a foul case of snowsphincter.”

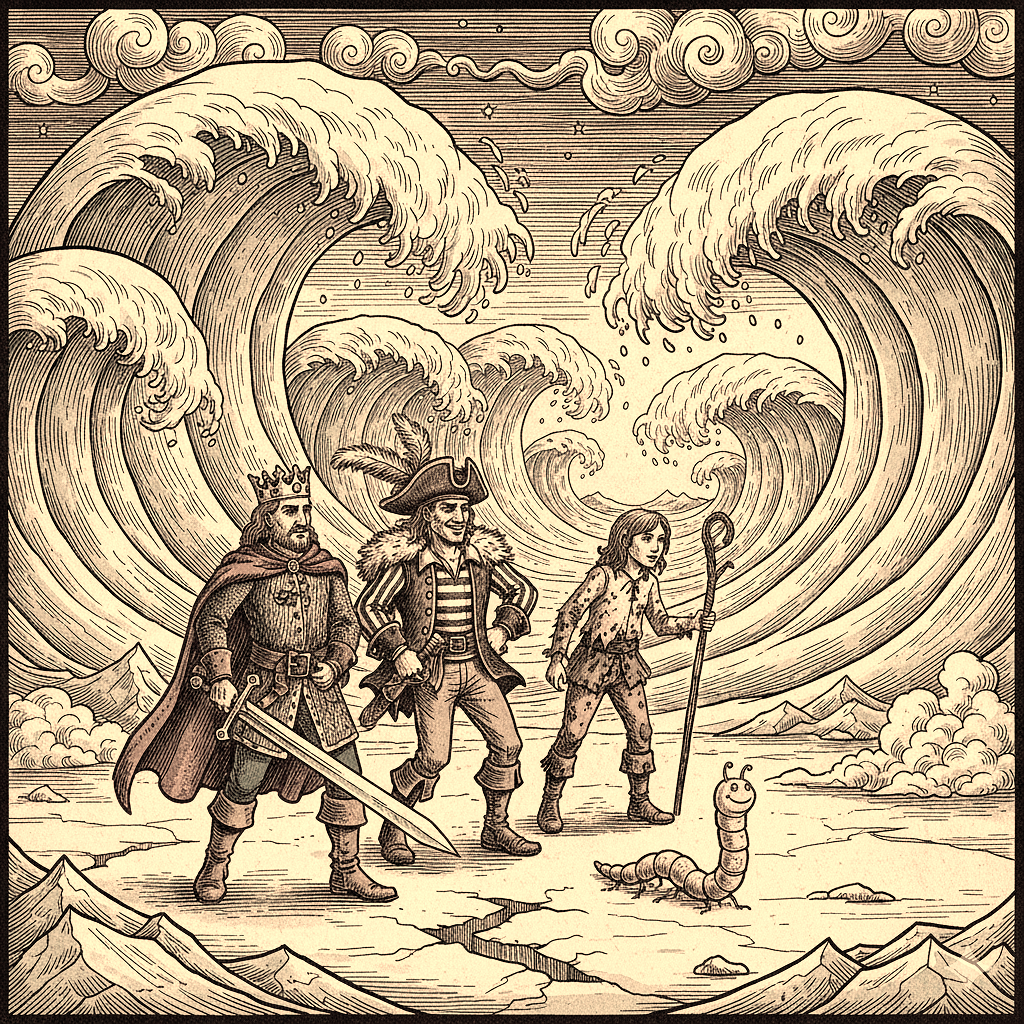

I clapped the book shut and tossed it over my shoulder, and a coarse spate of cursing in indecipherable colloquialisms told me I had accidentally clobbered Glob once again. We drew up to the edge of the Sea of Pìss and dismounted. Selladore lifted Edgar from his donkey and set him down gently beside us.

The waterscape before us was anything but peaceful in appearance; whenever the sea froze, whether caused by a wicked spell or Mother Nature just not giving a shit anymore, it had clearly been a stormy day. Ranks of waves the height of oak trees were frozen stiff, glowing blue-black with palpable malice. Their curled up foams were ragged like the curled legs of dead spiders, like a thousand screams frozen in time, like the world’s most aggressive lice comb.

“I reckon I’m not so sure about this Sea of Piss,” said Glob.

“Aye, nor I,” said Selladore.

Edgar didn’t say anything because he was rolling around in the mud emitting a soft happy squeaking noise.

“First of all, it’s pronounced ‘peace’,” I lectured. “And second, we have no choice. We cannot go back through the mines.”

“Why not?” asked Glob.

“Because… we just can’t. There are no famous heroes who shrugged and turned back three quarters of the way through their quests.”

“There are plenty of heroes who died three quarters of the way through their quests though,” said Selladore.

“Perhaps, but thou doth call them heroes just the same. We have to try.”

Never one to be outdone, Selladore rolled his eyes and flipped his boa over his shoulder.

“Fine. I bet one of us dies though.”

“Don’t be silly. Nobody is going to die.”